"Print" is a general term for an image made using a plate (wood, metal, stone, etc.) that has been engraved and inked, and then transferred onto paper using a press. A print can be made in several copies known as "proofs". Among the most popular printmaking techniques are lithography, which flourished during the School of Paris, screen printing, which continues today in street art, and engraving, like Rembrandt's metal engravings or Hokusai's Japanese woodblock prints.

A lithograph by Serge Poliakoff and a screen print by JonOne, which are among the most popular printmaking techniques.

An "original print" is defined as a print designed and executed on the plate by a single artist. However, many high-quality prints have been made by artists based on the works of other painters or draughtsmen, known as "interpretative prints".

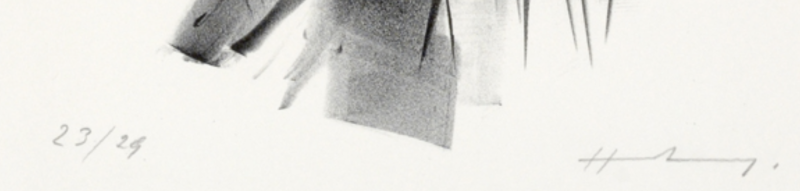

The handwritten signature of the artist and the print run justification, which appear in the lower margin, began in the late 19th century and became a standard for identifying the print run.

The proofs of the same print run are not perfectly identical, due to the manual intervention (inking, pressure). Apart from these final proofs, there are proofs that testify to the different stages of the plate's development, known as "proofs". The artist sometimes makes prints of a few proofs during their work, before reworking the plate to achieve the final result.

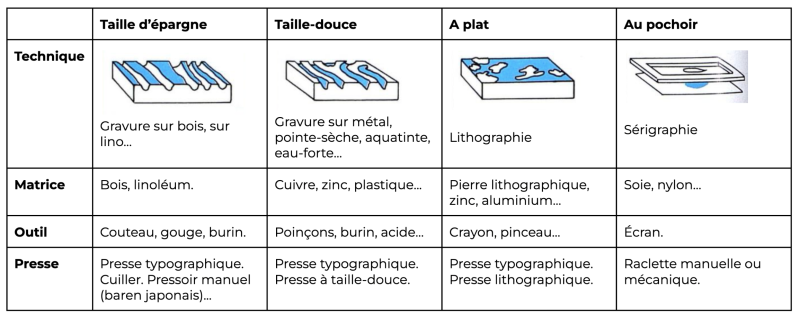

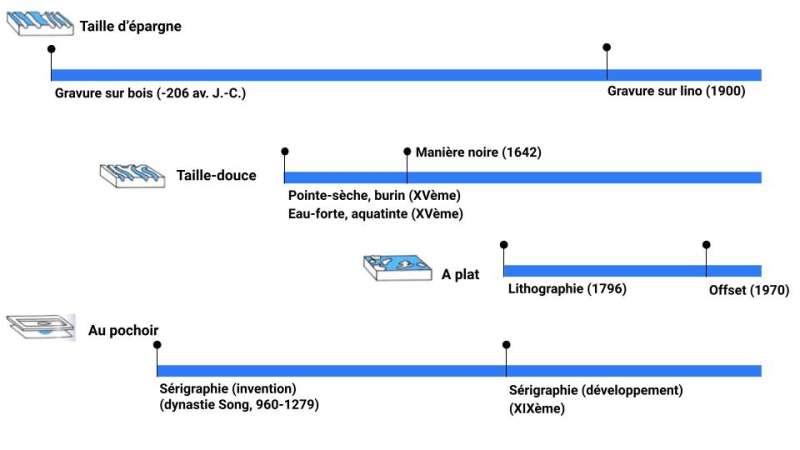

The different techniques leading to printmaking can be grouped according to the material used (wood, metal, stone, etc.) or the method of creation (manual or chemical), but the most classic classification is based on the type of matrix. The inks used for printmaking vary in composition depending on the printing techniques. For intaglio and lithography, slightly greasy inks are used to satisfy the affinity of copper or the drawn part of the stone. In screen printing, covering and opaque inks are mainly used, which allow for dense color flats.

Wood engraving is a process that appears quite simple, but can be extremely complex in practices like Japanese printmaking. The artist carves a plate of wood or linoleum using a gouge, a point, or a knife to remove material. The plate is then inked, and only the areas that have been spared will be visible on the paper. This is why it is referred to as “relief printing”. It's the same principle as ink stamps or potato stamps from our childhood! The complexity increases when a high level of detail is desired, which requires virtuosity from the artist, as wood is a resistant material. Moreover, if multiple colors are to be printed, a separate plate must be carved for each color. Then, each plate is printed on the sheet so that the colors overlap. This process is very meticulous, and a small millimeter of difference can distort the final result.Let’s now look at the two main matrices : wood and linoleum.

Although the process was known in China since the 7th century, its appearance in Europe dates back to the end of the 14th century. The woodblock is cut along the grain. By using several blocks, each representing a part of the design, and overlaying the prints on a single sheet, it is possible to achieve a color print. Wood engraving is recognizable by its sharp forms, due to the hardness of the wood, and sometimes by its slightly uneven flat areas, due to the wood surface not being perfectly flat.

A wood engraving by Hans Arp, Soleil Recerclé, on Auvergne paper, printed by the Féquet & Baudier workshop.

We observe the soft shapes and sometimes sharp angles. The roundness and uniform flat areas required significant engraving work.

This form of engraving is similar to wood engraving in terms of technique; only the material differs. Linoleum is softer to work with and much less expensive. Many amateur artists try their hand at linocut because it can be easily done at home. However, this technique also became popular among 20th-century artists, particularly Picasso, who elevated its status. The Andalusian artist developed a process to engrave multiple colors on the same plate. He would shave off a thin layer of linoleum to ink a new color, leaving no possibility for reversal !

This linocut of a woman's bust by Pablo Picasso demonstrates the technical range of the medium and the creativity of the artist..

Different techniques can be used for the same print. A polychrome print can be achieved either with a single plate by inking each part with different colors or by overlaying several plates, each for a specific color.

Drypoint is an engraving technique used to create a metal matrix with a sharp point. Together with the burin, it forms part of the direct engraving methods (where the artist engraves the plate with a tool), as opposed to indirect engraving where the plate is etched with acid. Both direct and indirect methods are part of the intaglio family, more commonly known as "metal engraving."

This engraving by Pablo Picasso contrasts the softness of the etching for the characters with the sharp line of the drypoint for the background.

The use of drypoint dates back to the 15th century. The name refers primarily to the tool, a simple steel point, with which the metal plate used for printing the proofs is engraved. Drypoint differs from other intaglio techniques in that it leaves burrs on either side of the incised line; these burrs make drypoint a hybrid process between intaglio and relief printing, as the ink settles both in the grooves and on the burrs.

This is the oldest intaglio engraving technique. Its origins lie in the impressions that goldsmiths made of their ornamental metalwork to keep a record of their work. Emerging in the mid-15th century simultaneously in Italy and Germany, this technique spread to other countries from the 16th century onward. The engraver carves into a copper plate using a steel tool called a burin. The design is thus formed by V-shaped grooves of varying depths. The plate is then inked and wiped clean. Under high pressure, the damp paper molds into the grooves, retaining the ink and creating a slight relief to the touch. The pressure exerted by the intaglio press leaves an impression commonly known as the "plate mark."

This process has been used since the 15th century. It is an intaglio engraving method on metal, typically copper, but also zinc or aluminum. The plate is covered on both sides with protective varnish; the artist, using a pointed tool or a well-sharpened pencil, draws on the varnish, exposing the copper where they make their marks. Once the drawing is complete, the artist immerses the metal plate in a bath of nitric acid or ferric chloride for etching. The depth of the etch varies depending on the acid concentration and the duration of the plate's immersion. The acid only affects the areas where the copper is exposed. The artist can perform several successive etchings to achieve different shades, and can also remove the plate from the bath, cover parts that have been sufficiently etched, and draw new lines. Etchings are often combined with aquatint for different effects.

The prepared metal plate is then inked and printed onto paper. For the artist, this engraving technique is more practical than direct relief engraving, such as with a burin. The point used to draw the design easily glides over the varnish. Etching allows for deep blacks and effects of texture and transparency that are appreciated by artists.

A harmonious etching by Georges Braque, depicting his famous bird motif.

Invented in the mid-18th century by the Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Leprince, aquatint achieves an effect that mimics wash drawing. The engraver sprinkles more or less coarse grains of resin onto a copper plate. The plate is then heated until the grains harden, making them resistant to the etching acid. The copper is then etched around the grains. This allows for the creation of shades by varying the etching depth and the fineness of the resin. This intaglio technique is recognized by the finely granulated appearance left by the resin. Aquatint produces a velvety finish and flat areas of color with a complex texture. Among the artists who have magnified this technique are Pierre Soulages and Serge Poliakoff. Some artists, like Bertrand Dorny, use the copper plate of the aquatint to emboss slightly moistened paper.

An aquatint by Pierre Soulages with a distinct character. The copper, extensively etched by the acid, imparts texture and relief to the paper.

This technique was discovered in 1642 by the German Ludwig Von Siegen. Mezzotint is a hybrid engraving technique that combines intaglio and relief. The copper surface is roughened with a multitude of small burrs using a semi-circular tool fitted with small teeth, known as the rocker, so that the initial print of the plate before the design is executed produces a perfectly velvety black. The actual drawing is done with a burnisher. The engraver flattens the grain of the burrs to achieve greys and completely removes them to obtain whites. Mezzotint engraving requires a lot of care, and the printing process is delicate.

This technique is synonymous with intaglio metal engraving. It also refers to the Chalcography of the Louvre, which holds a significant collection of engravings dating back to the 18th century. Today, the Chalcography of the Louvre continues its mission of preserving paper engravings and engraving techniques. It does so by publishing contemporary prints and reissuing old works.

This technique refers to a high-quality printing process capable of producing a large number of copies, originally used for printing art books and postcards. Grain heliogravure, on the other hand, is considered a precursor to photographic printing. It was invented by Nicéphore Niépce, and its name is inspired by the sun (the Greek god 'Helios'), in reference to the long exposure time required for the process. Although the process has undergone several evolutions, it fundamentally relies on engraving a copper cylinder, which is then inked and pressed against a sheet of paper. Heliogravure is distinguished by the high quality of its colors, the depth and subtleties of its blacks, and its ability to produce numerous prints from a single copper roll. It also played a key role in printing the earliest daguerreotypes, the ancestors of modern photography.

The lithography is a very popular printing process, used by artists from the School of Paris, especially Miro, Chagall, and Picasso in collaboration with the legendary Fernand Mourlot lithography workshop. The painter draws the design on stone (or a zinc plate), which is then inked and pressed onto the sheet. Artists can use familiar tools and techniques such as brushes, pencils, or washes. They can also scratch the stone to add additional effects. Each color requires a separate stone, and the design is reversed on the paper, which requires practice and the assistance of a lithographic craftsman. Some lithographs are not executed by the artists themselves, like exhibition posters that reproduce oil paintings. Therefore, the lithographic craftsman is an outstanding chromist, capable of interpreting a work on the lithographic stone.

This imposing Bacon lithograph reproduces a panel of a triptych that belongs to a private collection. The drawing on the stone allows for a wide variety of effects, from pure flat tones to very detailed areas.

The lithography (litho for "stone") is a technique invented in Bavaria around 1798 by Aloys Senefelder, which became successful in the 19th century. Based on the antagonism of water and greasy substances, this flat printing process consists of creating surfaces that retain greasy ink, and others that repel it.

This technique is the origin of offset printing, also based on the antagonism of water and greasy substances. On a fine-grained, regular porous limestone, artists draw with greasy ink. Then, the rest of the stone is treated to make it water-friendly; when the printer rolls ink over the pre-moistened stone, the ink adheres to the greasy parts drawn on the stone, while the areas meant to appear white reject the ink. To maintain this antagonism, the stone must be constantly moistened. To print, a sheet of paper is applied to the stone, which then goes through the lithographic press and undergoes friction that transfers the ink from the stone to the paper. Lithography allows artists great freedom of gesture and expression, especially for works "in the manner of pencil." Water and ink tend to emulsify, which is why artists who want intense colors often prefer screen printing, whose covering ink allows for better flat areas.

This technique, similar to lithography, uses a zinc plate instead of stone. The artist draws directly on the plate using painter's tools. Once the drawing is complete, the zinc plate is pressed onto a sheet of paper, reproducing the image in reverse. Zincography has the advantage of being more manageable than the heavy lithographic stone. It also allows the creation of larger lithographs, which would be difficult on stone. This technique was invented in 1813 by Alois Senefelder, who also originated lithography. The process was popular until its gradual decline in the 1920s. Among the painters of the second School of Paris, Hans Hartung is particularly renowned for his use of zincography.

Zincography by Hans Hartung, L 1971-6, on Rives vellum, printed by the Arte - Adrien Maeght workshop.

This technique, a variant of lithography, was designed to simplify the creative process for artists. The artist begins by drawing on special paper. This drawing is then transferred onto a lithographic stone. This process offers two main advantages. First, the paper is more manageable than the heavy lithographic stone. Second, the artist can draw the design directly the right way up. This drawing is subsequently mirrored onto the stone, and then again mirrored during printing on the final paper. This represents a significant advantage over the traditional lithography method, where the artist must draw the design in mirror on the stone so that it is correctly oriented on the printed paper.

Autography by Hans Hartung, L 30, on BFK Rives vellum, printed by the Jean Pons workshop.

This technique is a modern evolution of lithography, widely used for mass printing of magazines, advertisements, and catalogs, while also being used in the field of artistic printing. In practice, a digital design is transferred onto an aluminum or plastic plate fixed on a printing cylinder.

The offset process, which is photomechanical, however, offers lower quality than traditional lithography; the print pattern becomes visible when examined with a magnifying glass. Offset is therefore preferred for large limited editions (such as some works by Bram van Velde) or by contemporary artists who choose to adopt this mass printing technique. Since the 1980s, the term 'digital print' has also been used to describe works whose matrix is created by computer.

The technique of screen printing is widely used by illustrators and comic book authors to produce editions. They appreciate its vibrant colors and dense flat tones. Further back, among the artists of the School of Paris, Sonia Delaunay created numerous screen prints with the publisher Galerie Denise René. Screen printing allowed her to faithfully reproduce her interlaced color flats, her famous Colored Rhythms.

A signed screen print by Victor Vasarely, Phobos.

Screen printing is a printing process using a silk screen: it is a modern printing technique derived from the stencil method. The artist traces their design on the screen stretched on a frame using liquid latex. This latex is removable and can later be peeled off, leaving the silk mesh free. A sealing varnish is then applied to the entire screen surface, which aims to prevent the ink from passing through the screen in the areas that are meant to remain white. Once the varnish is dry, the artist peels off the latex film, thereby freeing the mesh that will allow the ink to pass through and deposit onto the paper. The ink is placed in the frame and forms a small wave that the artist moves from one edge of the screen to the other using a rubber squeegee. The artist will repeat this operation as many times as there are colors. The inks used for screen printing are opaque and covering, allowing the colors to be superimposed.

Here is a summary table of the main printmaking techniques:

The technique involves creating a matrix from plexiglass or cardboard onto which materials such as glue with varying fineness of sand (the famous carborundum), putty, etc., are applied to create textures. This support is then inked and passed through a press to achieve various printing and embossing effects.

Aquatint and carborundum by the engraver Antoni Clavé, printed by the Poligrafa workshop.

The artist uses sand to trace patterns on the matrix and print in relief on the paper, with carborundum offering a unique grain.

Aquagravure is characterized by the simultaneous creation of paper and engraving. The artist carves and sculpts their motif in low relief in a plate of wax, or other material like wood, metal, linoleum. The result is an embossed print, with strong reliefs, since the moist cotton fibers have been molded by the shape of the matrix.

Aquagravure by Cobra artist Guillaume Corneille. The paper relief conforms to the geometric shapes.

Stencil is the precursor to screen printing. It is a technique of cutting shapes in thin metal or cardboard to apply gouache with a brush without going outside the cut-out shape. Stencil is not a printmaking technique per se, as the sheet is not printed using a press. However, it allows for the creation of serial works, sometimes by the artist's hand, sometimes executed by a craftsman and supervised by the artist. Gouache is applied directly onto the sheet using the stencil, giving a texture similar to painting, beautiful flat tones, and vibrant colors. This technique is the origin of screen printing. The difference between stencil and screen printing lies in the mechanical aspect of the latter (though sometimes operated manually), unlike stencil, which is done by hand.

Stencil by Sonia Delaunay, Poetry of Words, Poetry of Colors.

The process of monotype is a painterly technique that allows painting directly on any type of plate with a brush and printing inks. It is printed either using a press or by hand, producing only one copy. It is, therefore, a unique work, sometimes numbered 1/1. The result is generally diaphanous, with muted colors, and a finish akin to watercolor.

A monotype impression by Gérard Panet. The pictorial qualities and unique texture of this medium are evident.

A intaglio technique where the copper is covered with a soft varnish onto which a textured paper is placed. The artist draws with a pencil on this paper, which adheres the varnish to the areas of the line. Then, etching is done on the copper exposed by the drawing.

An etching process by lifting the varnish: a mixture of sugar and India ink or gouache is applied directly onto the metal plate, which is then covered with varnish before being immersed in water: the sugar dissolves and lifts the varnish. The plate is then dipped in acid to etch the exposed parts.

Among modern papers - mainly mechanically produced - there is a range of papers of different qualities. Each paper is more or less suited to the various printmaking techniques. Thus, lithography is often printed on Vélin d'Arches, BKF Rives, or Pearl Japan; a Richard de Bas (handmade paper) or Lana Vellum will enhance a woodcut or etching. Some papers feature a watermark (a manufacturer's mark) in transparency; the watermark helps to identify the paper and sometimes to date it. It is possible that the printing of a print be done on different types of paper (for example, Vélin d'Arches and Pearl Japan).

If you have ever visited a paper mill, you know how paper is made by hand or machine. In short, cotton fibers are used to form a paper pulp, which is then shaped into sheets using a mold and dried. And there you have it, a sheet of paper, ready for printing!

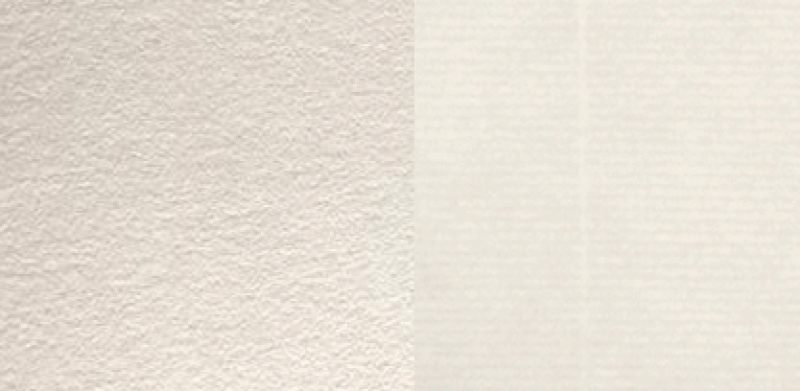

Let's examine the main types of paper used in printmaking. The most common is vellum paper, known for its strength and ability to print the matrix well. This paper is characterized by a fine and velvety texture, which enhances the printed image. It comes in different thicknesses or "weights". Among these, there are very thin papers, known as “parchment paper”, frequently used in restoration work.

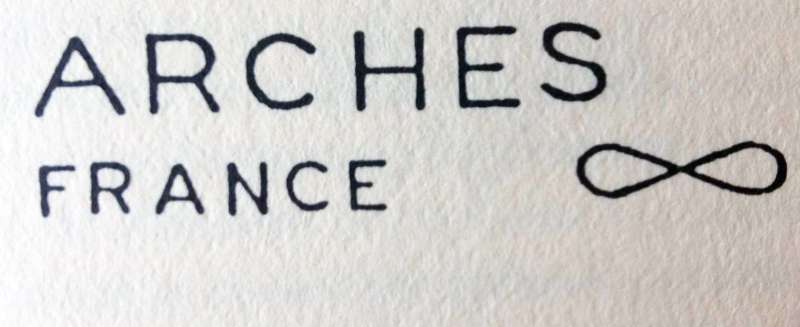

Among the most renowned manufacturers for printmaking are Arches, BFK Rives, Johannot, and Moulin du Gué. It's important to note that all these names have been associated with the Arches company since the 1950s, thus consolidating their reputation in the field of quality paper manufacturing for art printing.

Velvety vellum paper bearing an engraving by Seiko Tachibana

Moulin d'Arches was founded in the late 15th century, the era when Christopher Columbus discovered America. From its inception, the Arches company has been committed to producing high-quality paper sheets. While other manufacturers began integrating rosin into their paper for economic reasons as early as the 1820s, Arches maintained traditional methods, thus ensuring a durability of over a hundred years for its papers. According to Arches, in the 19th century, up to 90% of limited editions of artworks were printed on Arches paper.

Composed entirely of cotton, this paper presents a unique texture and can withstand multiple passes through the press, essential for color prints that sometimes require more than ten impressions. The round molding technique gives the paper fringed edges, that is, non-smooth edges. Additionally, Arches paper contains an alkaline reserve, protecting it against the acidity present in the wood of storage furniture or frames. However, it is advisable to store the sheets under appropriate conditions, away from direct contact with acidic materials like wood or cardboard.

In the 20th century, many artists from the School of Paris, such as Miro, Picasso, or Chagall, favored Arches paper for their prints, due to its quality and longevity. The name and watermark of Arches are marks of distinction that you will frequently find on the prints of these artists, ensuring the work's longevity over time.

An exceptional large-format lithograph by Joan Miro. The thick and velvety Arches paper accentuates the colors and textures of this artwork.

BFK Rives, named after the initials of its founders, is a paper mill located in Rives, Isère. It was active from 1920 until the mid-20th century, before being eventually acquired by its competitor, the Arches company. BFK Rives specialized in the production of papers similar to Arches Vellum, with a particular emphasis on a smooth grain designed to be discreet and enhance the printed work. This paper, known for its exceptional qualities in intaglio engraving, is ideal for works rich in detail.

Like Arches, BFK Rives saw significant growth through public orders, notably for the production of banknotes and administrative documents. The last BFK Rives mill in Rives closed its doors in 2011. However, BFK Rives paper continues to be manufactured by the Arches company.

Like Arches paper, BFK Rives features an alkaline reserve and fringed edges. These characteristics make it a favored choice for prints and art impressions.

An etching by Max Ernst. The BFK Rives paper, with its very fine grain, is ideal for bringing out the textures of the etching and the precision of the line drawing.

Laid paper is also available, recognizable by the visible lines, left by the manufacturing mold.

Comparison between velvety vellum paper and laid paper with visible lines

There are also special papers such as heavyweight board, colored papers, kraft, and Japanese paper, which can add a unique touch to a work. In Japan, the artisanal paper-making tradition, centuries-old, is becoming scarce. Artisans still active in this field are sometimes recognized as 'living national treasures'. The specialty of Japanese paper, known as Washi, lies in its composition of Japanese mulberry fibers (Kôzô). These long fibers, interwoven in all directions, give the paper remarkable strength. Japanese paper can also be extremely thin, offering a wide range of textures while maintaining exceptional strength. This type of paper played a crucial role in the spread of famous 'Japanese prints', such as the woodblock prints of Hokusai and Hiroshige, which inspired the Japonism movement. This discovery also captivated artists from the School of Paris, like Braque or Picasso, who were drawn to the quality, durability, and sensual texture of 'Japanese paper'.

A print by Georges Braque on nacreous Japanese paper, also known as Washi. The paper's veins, due to the fibers of the Japanese mulberry tree (Kôzô), are observable

The history of paper traces its roots back to China, where it was invented around 500 BC. Initially made from hemp fibers and tree barks, paper represented a revolution in the preservation and dissemination of knowledge. Its production and usage quickly spread across Asia, notably through the trade and cultural exchanges facilitated by the Silk Road.

The Arabs, having acquired the papermaking technique following their conquests in Central Asia, introduced significant innovations. Among these was the use of the wire-frame mold, which allowed for more efficient and uniform paper production. These improvements played a key role in the spread of paper to the West.

Europe saw the establishment of its first paper mill in Cordoba during the Middle Ages, a period when paper was still a luxury item. Cordoba, under Arabic influence at that time, became an important center for paper production in Europe.

In order to reduce their dependence on paper imports from Spain, the Germans and French began establishing their own paper mills over the following centuries. Among these mills, the Arches Mill in France, founded in 1492, became renowned for its high-quality paper production.

With the advent of printing by Johannes Gutenberg in the mid-15th century, the demand for paper increased exponentially. This led to the development of new papermaking techniques in the 18th and 19th centuries, including the invention of the paper machine by the Frenchman Louis Robert and its refinement by the British Henry and Sealy Fourdrinier. These machines revolutionized paper production, making it faster, more efficient, and more economical.

Ultimately, these innovations made their way back to Asia, where the paper machine was introduced, marking a return to the origins of this invention. Thus, the development of paper, from its humble beginnings in ancient China to its central role in modern communication and culture, illustrates a fascinating historical and technological cycle.

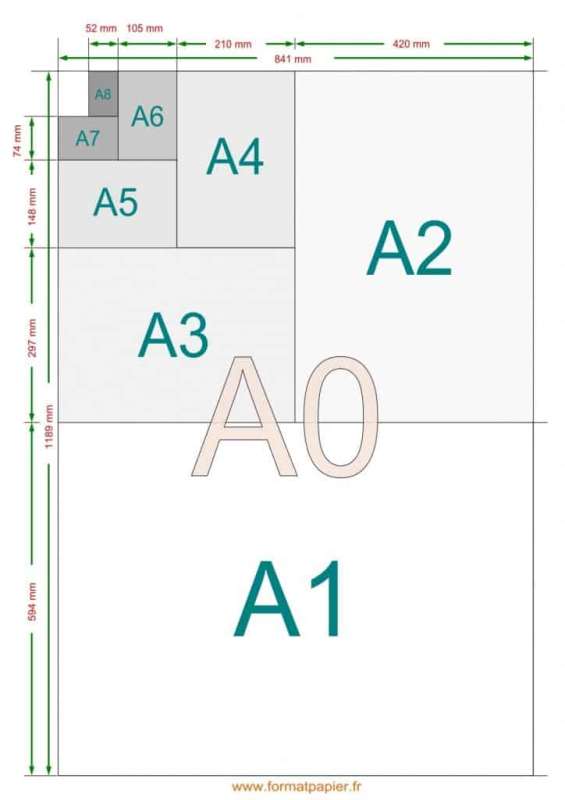

The A4 sheet is well-known to all, but in the field of printmaking papers, a multitude of other standard dimensions exist. In addition to the internationally widespread A series formats (like A3), there are also traditional French formats such as Raisin, Jésus, and others. Moreover, Japanese printmaking uses specific formats that differ from these Western standards. Furthermore, there are numerous custom sizes that do not conform to any established standard. Here is a table of correspondence between the A series formats and traditional French formats:

Demi-raisin 32.5 × 50 cm

Raisin 50 × 65 cm

Jésus 56 × 76 cm

Colombier 60 × 80 cm

Petit Aigle 70 × 94 cm

Grand Aigle 75 × 105 cm

Grand Monde 90 × 126 cm

Univers 100 × 130 cm

Grammage does not refer to the thickness of the paper, but rather to its surface mass, meaning the ratio of the paper's weight to its area. It is expressed in grams per square meter (g/m²). The higher the grammage, the thicker and heavier the paper generally is. Here are some common grammage examples:

Papers…

Cigarette paper: around 15 g/m²

Newspaper: 40 g/m²

Printer paper: 80g/m²

Vélin d’Arches: from 120 to 400 g/m²

Softcover book cover: 250 g/m²

Watercolor paper: 500 g/m²

The watermark on a paper is a distinctive mark embedded within the paper itself. It can be the manufacturer's logo, the name of the paper range, or other specific designs. This watermark becomes visible when the sheet is held up to the light. It's created by fixing a brass wire pattern onto the mold or screen used to form the paper sheet. During production, less paper pulp settles at the design, allowing the watermark to be visible. The primary purpose of the watermark is to authenticate the paper's origin and quality, and in some cases, to prevent counterfeiting.

Let's take a look at the exceptional mills, the main producers of vellum paper used for printmaking.

The Arches Mill

The Arches mill, famous for its high-quality vellum paper, has played a significant role in printmaking history since its establishment in 1492, providing paper for iconic works such as the Nuremberg Chronicles illustrated by Dürer. Under the direction of Beaumarchais, the mill even printed the complete works of Voltaire. In the 20th century, it became the preferred choice for Miro's or Picasso's lithographic works at the Mourlot studio.

The Arches mill, famous for its high-quality vellum paper, has played a significant role in printmaking history since its establishment in 1492, providing paper for iconic works such as the Nuremberg Chronicles illustrated by Dürer. Under the direction of Beaumarchais, the mill even printed the complete works of Voltaire. In the 20th century, it became the preferred choice for Miro's or Picasso's lithographic works at the Mourlot studio.

The Arches mill, famous for its high-quality vellum paper, has played a significant role in printmaking history since its establishment in 1492, providing paper for iconic works such as the Nuremberg Chronicles illustrated by Dürer. Under the direction of Beaumarchais, the mill even printed the complete works of Voltaire. In the 20th century, it became the preferred choice for Miro's or Picasso's lithographic works at the Mourlot studio.

The Arches mill, famous for its high-quality vellum paper, has played a significant role in printmaking history since its establishment in 1492, providing paper for iconic works such as the Nuremberg Chronicles illustrated by Dürer. Under the direction of Beaumarchais, the mill even printed the complete works of Voltaire. In the 20th century, it became the preferred choice for Miro's or Picasso's lithographic works at the Mourlot studio.

The Moulin du Gué, Johannot, and BFK Rives papers are no longer producing mills, but have now been integrated into the Arches Mill as paper ranges.

The Moulin du Gué paper range is specially made for intaglio printing. The three small flowers present in the watermark symbolize the 15% linen used in the paper's production.

For over four centuries, the Lana Mill, located near Arches, has maintained its reputation as a producer of high-quality paper. Mainly known for its fine packaging paper, the mill also manufactures cast papers highly regarded for printmaking. Additionally, it offers custom watermarks, adding a unique touch to its products.

Among international paper producers, the Hahnemühle Mill is particularly esteemed by artists working on paper. This ancient mill, founded in 1584, initially served to supply paper to the administration of the Duchy of Brunswick in Germany. The mill's founder, Carl Hahne, gave his name to the paper and its logo, which depicts a rooster (Hahn in German).

We can also mention the Whatman Mill in the UK, the inventor of vellum paper, the first smooth paper that doesn't show the horizontal thread marks of the paper mold (the laid lines of laid paper).

The renowned Richard de Bas Mill, producer of Auvergne paper, or handmade paper. In the 15th century, Auvergne had about fifty mills, and its central location favored paper trade.

Particularly high-quality, this paper was used to print the engravings of Diderot and d'Alembert’s Encyclopedia.

Pictured here, the wire that leaves a watermark on the paper.

There is often confusion about what makes a print "original." Is a print a reproduction of an original work, or is it original in itself? This notion has nuances, but in short, the term "original print" refers to prints that are created, supervised, and signed by the artist, or simply supervised and signed.

To structure commercial practices, the Chambre Syndicale de l’Estampe, du Dessin et du Tableau (CSEDT), which defends the interests of print dealers and their clients, has produced a charter of the original print. Here is an excerpt:

“An original print is a plastic expression voluntarily chosen by the artist, existing in several copies, according to the artist's will. Prints not made by the author of the signature or under their constant supervision must be clearly indicated as 'interpretation prints.' The contemporary original print is generally signed and numbered, unlike the ancient print.”

Charter of the Original Print, CSEDT, 1996.

To better understand what makes an original and authentic print, let's look at three types of prints: first the original print, then the interpretation print, and finally the photo-mechanical reproduction.

Unlike the interpretation print (made by a third party, engraver, or lithographer), for the original print, the artist himself conceives and creates his work on the matrix (stone, copper, steel, zinc, wood, or silk). Naturally, the original print encompasses all possible graphic expression techniques (lithographs, engravings, silkscreens). In the case of an original print, the artist creates the matrix himself and entrusts the printing to the printer. This is the case with Miro's lithographs, drawn on the stone by the artist and printed by the printers of the famous Mourlot workshop. Once the edition is printed, the artist checks the print run by signing each copy.

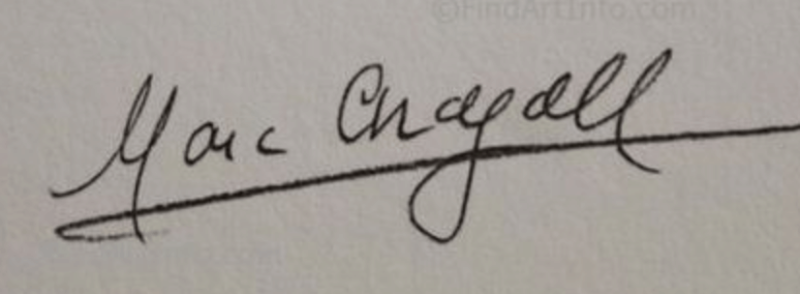

The original work of an artist (painting, drawing, etc.) is interpreted and transposed onto the matrix (support) by a lithographer or an engraver. This work is most often done under the direction of the artist himself, who sometimes places his signature on the print. The fact that the artist did not engrave himself from his work onto the matrix (stone, copper, etc.) is not necessarily linked to the value of the said print. For example, the beautiful interpretation lithographs of Marc Chagall by the lithographer Charles Sorlier from the Mourlot workshop.

This is the reproduction of a unique work or a print by a modern photo-mechanical process and not by a traditional printing technique. Photo-mechanical reproductions are generally not considered original prints. This facsimile, authorized or not, is commonly called "reproduction," "poster," "offset," etc. Some of these editions are still valued by the market. There are also many more or less legal counterfeits. It can be photomechanical reproductions produced for commerce (for example, editions made for museum shops), or even fakes intended to deceive. It is therefore important to be careful not to inadvertently acquire such a reproduction.

It's important to remember from this typology that the artist is more or less involved in the printmaking process. The minimum for an original print is that the creation is supervised by the artist, and they approve the print run by signing it.

To summarize, let's hear from the famous lithography printer Fernand Mourlot:

“An original lithograph is a lithograph executed by the artist, that is, he himself draws on the stone or zinc with a litho pencil or with a brush and water.”

"If the artist attended the creation of his lithograph, even if he did not make it entirely by himself, if he approved it, made corrections, gave his final approval, followed the printing process and signed the lithograph, it is considered an original lithograph."

Fernand Mourlot, Gravés dans ma mémoire, Robert Laffont, 1979.

How to guard against fakes or reproductions?

Here are some tips to ensure you are purchasing an original print, whether signed or not. It can be intimidating to navigate through the many prints offered on online platforms, or on second-hand sale sites, but these tips can help minimize problems.

If possible, buy your prints from a reputable gallery. If they have a physical space, you can see the print yourself. Recognized print galleries are members of the Chambre syndicale de l’estampe (CSEDT).

Check that the print you are coveting appears in the artist’s catalogue raisonné, with the correct dimensions and edition number. An artist's catalogue raisonné is a work listing the artist's works, established by specialists, which helps to understand the rarity of a print and identify fakes.

Catalogues raisonnés are not always easily accessible, but you can ask your gallery for a photocopy of the catalogue. There are also many available online, like those of Hans Hartung, Anna-Eva Bergman, or Sam Francis.

Second-hand sites like eBay or Leboncoin, as well as some e-commerce platforms, offer original works but also photomechanical reproductions and even fakes. It's risky to acquire a print this way. If a print is very cheap compared to the market price, it's probably “too good to be true.”

In the field of interest, "print" is synonymous with "proof" or "copy." A complete print run of a work is an "edition." The origin of this term comes from the action of pulling the arms of the printing press towards oneself. A "limited edition" means that the printing of the print is carefully controlled by the artist, and each copy is numbered. Once the publisher's defined print run is reached, the matrix is destroyed, to guarantee the limited nature of the edition.

The justification of the print run is the complete enumeration of the print run of a work; the actual numbered prints, the number of artist's proofs, proofs outside of commerce, additional prints on different papers, etc. The justification is available from the publisher, on authenticity certificates, in the catalogue raisonné, and for artist's books, in the colophon.

It is customary to print artist's proofs in addition to the normal edition: these are intended for the artist and the publisher as archives. Their number generally does not exceed 10% of the total print run. The artist's proofs, or "E. A." can be numbered, in which case they are in Roman numerals. The acronym "H.-C", for "hors-commerce" is also used. Finally, some prints have several states, meaning successive versions that can be edited, or that are printed only to check the composition. The most famous example is Picasso's bull printed by the Mourlot studio, with its 11 successive states!

Let's zoom in on the bottom of a print. Traditionally observed in the lower left corner is the numbering of the proof out of the total print run 23/25 (excluding off-commerce prints). And on the opposite corner, the artist's handwritten signature in pencil. Some artists place in the middle the title of the work, or the date.

A common question is: what is the value of the numbering? In our example, does proof 23 have a different value than proof 1 or 25? Well, no! It should be noted that prints are usually numbered by the printers, and they are not necessarily numbered in the order of printing. This tenacious misconception comes from traditional wood or metal engraving, where the fragile matrix wears out over the course of the print run. In this case, the first proofs are more qualitative than the last.

One might also wonder what represents a "large" or "small" print run. Generally, a print run of less than 150 copies can be considered limited. Beyond that, the print run is less rare, like some editions of posters with 2000 copies. There are also more confidential print runs, like that of Hans Hartung above, or the editions of Picasso's prints, often printed in 50 copies.

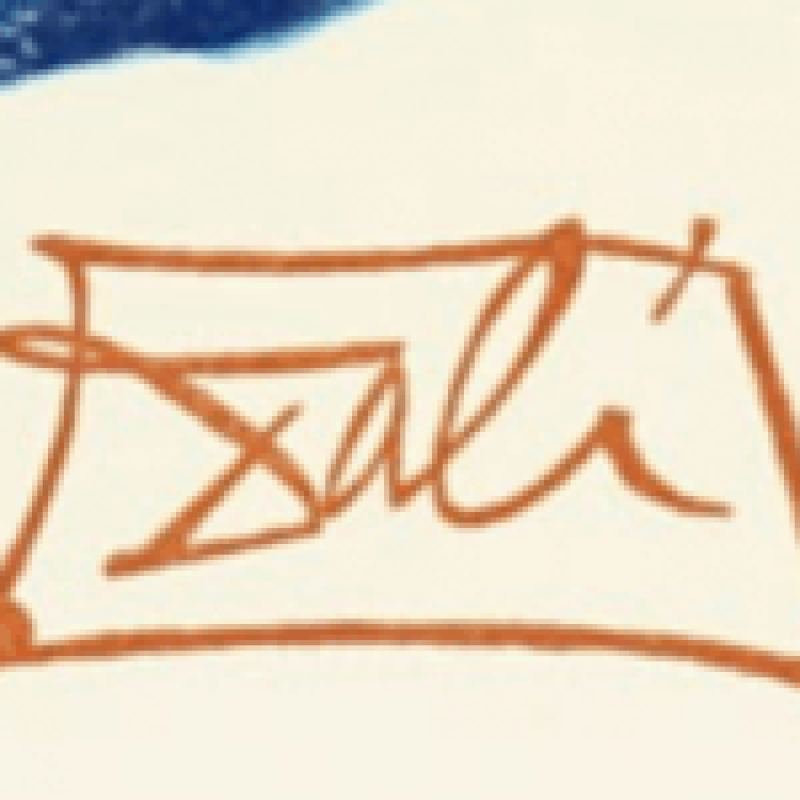

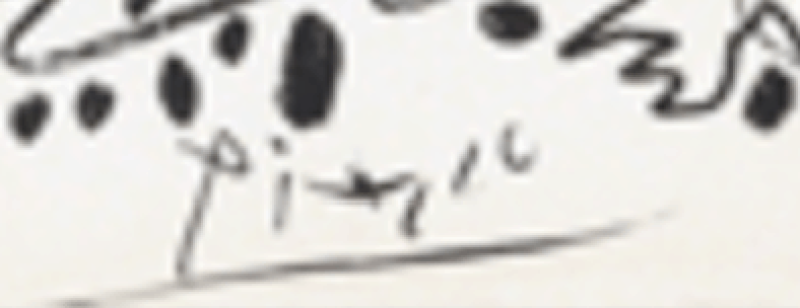

In the field of modern printmaking, usually at the end of the printing process, the artist places their signature in pencil on each of the proofs. This step allows them both to control the print run and eliminate proofs that do not fully satisfy them. Not all artists enjoy signing, like Francis Bacon who was reluctant to sign the prints of his interpretations, but it is a mandatory step to guarantee the limited nature of the print run and the quality of the individual proofs. In the world of printmaking, the following anecdote is often relayed: unscrupulous publishers had artists sign blank sheets, particularly the artist Salvador Dali, with the intention of printing and selling lower-quality prints. Fortunately, this practice is no longer common, and serious publishers and dealers sign a charter for original prints, which prevents such fraudulent practices.

Additionally, some prints bear a printed signature, i.e., applied by the artist within the composition (for example, in the stone for lithography or in the copper for engraving), which does not necessarily exclude an original signature. It is also said that the signature is "in the plate," or it bears the "artist's stamp."

There are unsigned prints of original artworks, using the same matrix as for the signed print run. For instance, this is the case for lithographic illustrations in art magazines or illustrated books, which flourished during the time of the first School of Paris. Notable examples include the journals XXème siècle, Les Cahiers d’Art, founded by Christian Zervos, the author of Picasso's catalogue raisonné, or Derrière le Miroir published by Maeght.

These prints not bearing the artist's signature are just as original and qualitative as the limited and signed prints. They are a good way to acquire beautiful pieces at a lower cost. It is then understood that an artist's signature on a print greatly increases its value: its price, but also its potential as an investment.

Let's now take a look at some artists' signatures and stamps:

Printmaking has its roots in Asian tradition, where it was used by monks to reproduce texts and images using woodblock printing techniques. The oldest known print, a woodblock print on silk, comes from the Han Dynasty and is estimated to have been produced between -206 BC and 220 AD.

In Japan, woodblock printing technology arrived from China around the year 700, and it was used to reproduce foreign literature. Woodblock printing widely developed during the Edo period (1603–1868) as part of the aesthetic movement Ukiyo-e, the Japanese print as it is known in France. It was used to depict famous views of Japan, battles, and genre scenes.

In Europe, the first prints were also wood engravings. In 15th-century Germany, woodcuts were used to print playing cards.

Artists quickly embraced the technique, and printmaking flourished in the 15th century, representing a major advancement for Western art, enabling the multiplication of images. This was before Gutenberg's printing press!

Metal engravings, more robust than wood for printing and allowing finer lines, became widespread around the 1430s, again in Germany. The technique flourished among the first great master engravers at the end of the 15th century, like Albrecht Dürer. And around 1450, the famous Johannes Gutenberg invented movable type printing, a true revolution, enabling mass book printing. The Gutenberg Bible is the first book printed with this technique.

In the 17th century, Italian artists experimented with indirect etching techniques, using acid to corrode the metal plate. They perfected the technique of etching already practiced by Albrecht Dürer in the 1510s. Mezzotint, a process allowing natural grey levels, was invented in 1642 by an amateur German engraver. Some artists, like Rembrandt, exploited metal engraving to great effect. Gradually, French engraving would experience its golden age, becoming an affordable and fashionable art. The French Revolution used engraving as a vehicle to widely disseminate its ideas.

In the 18th century, Italy remained the cradle of European printmaking, with master engravers like Tiepolo, Canaletto, and Piranesi pushing the technical limits of printmaking. In Spain, the first great Spanish engraver, Francisco de Goya, turned to etching and lithography late in his life, producing a personal work that would inspire modern art, particularly expressionism.

From the 19th century onwards, the emergence of lithography gave a new impetus to printmaking, continuing to this day. This technique, invented by the German playwright Aloys Senefelder, is easier to master than engraving and allows printing more copies than the copper plate, which quickly wears out.

By the late 19th century, the era of painter-engravers who excelled in both disciplines began, pushing the boundaries of printmaking. We can mention the Nabis, Bonnard, and Vuillard, as well as the post-impressionist painter Paul Gauguin, up to the painters of the School of Paris like Miro, Chagall, and Picasso, renowned for their print work. This was also the reign of color, with the prints of Fauvists and German Expressionists. The multidisciplinary mastery of painter-engravers allowed them to enrich their practices and offer varied aesthetics and complete works.

To conclude this history, let's mention that linocut appeared in 1900, while the material used for floor covering had been invented at the end of the 19th century. On the other hand, screen printing has a very long history, having been invented in China during the Song Dynasty (960-1279). At that time, stencils cut from silk (“seri” means “silk” in Latin) were used to print proto banknotes. With this long tradition, Chinese immigrants introduced this technique to the United States in the 19th century, where screen printing experienced a surge among Pop Art artists like Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, and Roy Lichtenstein.

Here is a summary in the form of a timeline:

We have reached the end of this printmaking guide. We hope that your understanding of the various printmaking techniques and how to collect them has been refined. Most of the prints featured can be found on our online gallery, or you can visit us in our galleries in Le Marais or Saint-Germain-des-Prés.

Luc Bertrand, for Le Coin des Arts Gallery - Thaddée Poliakoff Fine Art

Secure payment

3DSecure 2.2

Free DHL Express delivery from €1,200

Carefully prepared parcel

Parcel tracking

Shipment insured

for the value of the artwork, covering theft and damages

Fairest prices

Certificate of authenticity

Two galleries in Paris

Receive an email as soon as a new artwork is added for this artist

Your message has been sent ! We will get back to you as soon as possible.

Please fill in the form if you need further information such

Please fill in your email address, an email will be sent with a link to update your password.

You can now place orders and track your orders.